Like sentinels, Koryaksky, Avachinsky and Kozelsky stand watch over the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. As a mountain adventure lover, the beauty and allure of these volcanoes cultivate the imagination. Going about your daily business, walking to the shops or riding in the bus, occasionally the red glow of a sunset on the jagged peak, or the white fumaroles billowing out of the crater will catch your eye, and hold you in fascination.

From December through to March I was living on the Kamchatka Peninsula with my girlfriend (now fiance!) Anna, who is a local there. There has been plenty of time for adventure, and I've been able to get out on many interesting backcountry ski trips close to the city, with Anna and her friends. Even so, with more time on my hands than most, and the desire to get out and explore the place, I found myself heading out on more solo trips. I've previously written about my desire to find partners for trips when I was in New Zealand last year, and have since had more time to reflect on this topic, and the events of that season.

As February rolled on in, Kamchatka has experienced, what I am told is, an unseasonably long spell of fine weather, several weeks without significant snowfall, with a decent depth of snow already in place. From an avalanche perspective, exploring some of the larger peaks in the area wasn't seeming like such a bad idea, despite it still being February. Generally they come into season in Spring. A recon trip (and Christmas gift from Anna) to Avachinsky pass on the 2nd of January on snowmobile had not revealed any visible recent evidence of activity over the wide range of aspects and elevations visible, other than perhaps a crown line up near the summit of Koryaksky up at about 3200m. There was one main problem, I didn't yet have a partner for such a trip. Experience and reflection has gradually made me more cautious when considering travelling with a new partner on serious mountains (where the consequences of a mistake could easily be fatal). For several reasons finding someone who is available and that I can trust this time was proving difficult.

Several factors were not working in my favour here. I don't speak fluent Russian, and not many people in Kamchatka speak fluent English. Communication with your partner is of prime importance in the mountains, problems understanding each other can easily lead to big mistakes, and awkward situations at the least. This is my first time to Kamchatka in the Winter, and I have not had much time to meet new partners and build up a history and mutual understanding on smaller trips. I have bucket-loads of free time and am lucky to be in a position where I can look at the snow conditions and the weather forecast, and choose the best day for a given trip. Not everyone has this luxury, and I would warrant there aren't many people staying in Kamchatka with a similar plan (ski/explore as much as possible for several months) that I could possibly find and join forces with, unlike other more popular ski destinations.

And so the thought of going alone (already having several solo trips in less serious terrain under my belt) began to germinate. I talked earnestly with with some friends, and read some interesting articles on the topic. I noticed that some people appear to state strong opinions without presenting carefully chosen arguments. How much riskier is going solo vs skiing with a partner/partners? How does this risk level/comparison vary depending on, personal experience, what terrain will be covered, what the snow conditions are like, and who potential partners are? Does the presence of a two way satellite communication device (such as an InReach) offset some of the additional risks of travelling solo, to within one's personal risk appetite/boundary?

Ski or board backcountry alone? Don't be an idiot offers one perspective, with a very strong tone of warning. One personal take-away from this article was that accidents such as tree-well deaths, and suffocating in deep Japow are prime examples of situations where having at least one partner would go a great way towards preventing an embarrassing way to die. The high volcanoes here in Kamchatka generally don't appear to exhibit such deep powder (usually being very windswept), and there is a distinct lack of trees, or for that matter, trees capable of producing tree-wells. On a similar topic, the lines I was considering were not glaciated, so falling into a crevasse was also a minimal possibility.

The author observed some solo travellers exhibiting overconfidence, a lack of knowledge, and other psychological traps, making them more susceptible to succumbing to an accident. They also observed that even experienced and careful people travelling solo can be caught and killed by a slide. These observations, while certainly important, need to be placed in context with statistics and other considerations, because, as most people who have done some avalanche education will be aware, generally these factors could just as easily apply to groups as they do to solo travellers. Groups also provide grounds for other risk factors to arise (unhelpful group dynamics/personal interactions).

Obviously, and perhaps most importantly, travelling alone basically throws out the possibility of rescue after burial in an avalanche. A beginner who is unable to comprehend the risks, and makes a lower percentage of correct decisions in the backcountry statistically relies much more on the experience of others and the safety net provided by their partners in the form of companion rescue. I'm aware that despite having taken some avalanche courses, I am still a relative beginner and I am the perfect candidate for an avalanche victim, a confident Male in my 20's, willing to take some risks, perhaps more than others.

Considering this further, how does the number of partners affect your chances of being rescued in the event of a slide? If the slide path is large/long, and your route makes it likely for multiple partners to be exposed during the ascent or descent despite best management practices, will one or two partners be enough to rescue you? What is the runout like? Are there cliffs below? Is the possibility of avalanche unacceptable regardless of whether or not you have partners available for rescue? These questions make me think more about the psychological bias of "safety in numbers", and how it has applied to group trips I've been on so far. During my recent course in New Zealand, I also learned that in order to have a reasonable chance of surviving a long career, a professional working in avalanche terrain needs to rely very much on making correct/cautious decisions every time they go out (or choose not to go out), they cannot afford to play Russian Roulette (pun kinda not intended!), no matter how good their partner's rescue skills may be. In a guiding situation, I imagine that a client's rescue skills could be fairly low anyway, and a potentially fatal avalanche involving a client may reap even larger consequences for a guide than a personal accident with friends.

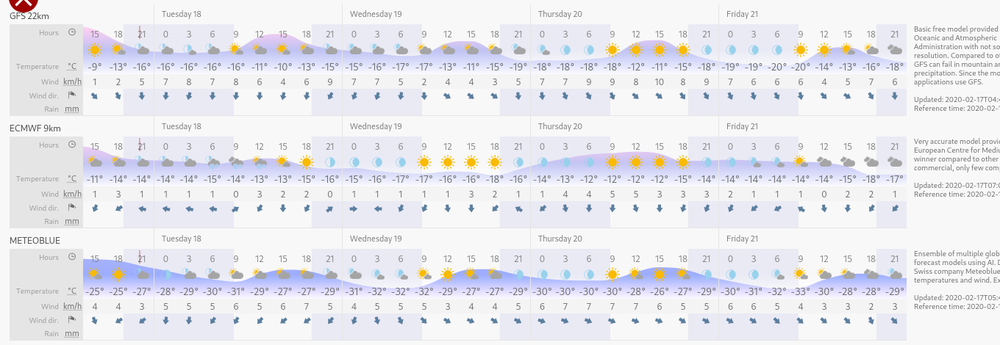

On the 19th of February, with the weather continuing to look good in all the forecasts, I hitched a ride with a snowmobile group from Kamchatka Freeride Community up to the Avachinsky base (870m), with a non-committal plan to explore some of Koryaksky and Avachinsky. I was aware that there had been some new snow a few days earlier, but wasn't sure how much had fallen, and how much wind transport had occurred during the days following.

After a quick chat in broken Russian over some hot tea with an old couple living in one of the bases about my desire to stay there for a couple of nights later in the trip, I stepped out into bright sun and skied up the valley towards the pass. A quick snow pit examination during lunch revealed that there had been a fair bit of new snow, and the possibility of wind slab was certainly something to be looking out for. I stuck to the ridge line and made my way up the lower angle slopes at the base of Koryaksky, I felt dwarfed by the peak above, progress seemed impossibly slow despite the sun making tracks across the sky. In the evening I was pretty well convinced that wind slab would be a concern higher on the peak, so I selected a sheltered camp in a hollow on the ridge at about 1600m. It was enthralling to be up high with hardly a breath of wind and perfect visibility over the Pacific Ocean and down to the southern end of the peninsula. I'm so glad there was no wind because it was very cold, my stove refused to start (rated to -20C), so I spent a good 30 minutes running up and down the hill with it in my jacket before cooking dinner.

Being solo removes the the possibility of a partner initiating critical first aid for an unconscious person and calling in or performing a rescue on behalf of this person in the event of a serious mishap during a trip. This is perhaps an unavoidable crux for the question of travelling solo, a risk you must accept regardless of the trip planning/preparation. Originally a sceptic, I recently bit the bullet and purchased an InReach Mini after learning that a PLB may not be legal to use/carry in Russia due to its use of restricted radio frequencies. This device is a great improvement on communication. I can enable tracking and have someone at home watch my progress, and check on me. I feel that this does go a little way towards the offsetting this risk on solo trips. In any event, a serious accident is a situation that will likely require external rescue help, as one or two partners will have a very difficult time performing an effective rescue from a remote location. If there is a minor mishap, which can be solved without a full-blown rescue, the improved communication of in InReach can also be much more useful than a PLB. I guess it should go without saying, that it is always important (whether solo or in a group), that someone external knows the plan, and is able to call rescue and give accurate information if something goes wrong.

Some other things I can think of which might help offset the risk of mishap is to ensure you are adequately fit, and moving quickly and efficiently, and don't push yourself beyond your limits, turn around before becoming exhausted. Watch the weather, and conditions carefully, try not to pick a day where it is working against you. Pick objectives that are reasonable for your ability, and avoid the temptation to be committed skiing a given line or summiting a given peak. All the general precautions and risk management techniques that apply to group trips, should be carefully applied to a solo adventure where possible.

In the article After avalanche deaths, experts renew call for climbers to carry safety gear the author discusses the choice of many climbers to travel without an avalanche beacon while in avalanche terrain in order to save weight, and with the argument that if there is an avalanche they would likely be killed anyway. It encourages people to consider wearing a beacon at all times anyway in order to aid rescuers in the event of a body recovery, and on the chance that a companion rescue may be possible if the slide occurs on less serious terrain.

Rescuers put their lives at risk, and sacrifice their time to search for missing people in these situations, and I guess as a solo traveller, wearing a beacon, and tracking your location with an InReach is the least you can do to make it safer and easier for a rescue team to find your body, to help avoid yet more tragedy. Perhaps the grim task of putting on a "useless" avalanche beacon in the morning may serve as yet another reminder of one's own mortality, and how important decisions during the trip will be.

I woke up, and unzipped the tent door to be welcomed by the sunrise gleaming through the smoke of the fumaroles on the summit of Avachinsky. It had been quite a cold night despite wearing all clothes, and down jacket over the top, I regretted not taking some extra insulation for under my legs. My hopes for an early start were dashed when I retrieved a very frozen stove from the bottom of my sleeping bag that took quite a long time to get started again. By the time I had my tent packed it was pretty obvious I wasn't likely to be making summit that day, almost another 2000m above.

As I continued up, ice, followed soft snow over exposed rocks on the ridge required the removal of skis, and made progress incredibly slow. It was getting to about lunch time again, at about 2150m I dug a pit in the gully on the side and found yet more wind slab with a thick layer of facets near the base this time. The decision to turn around and save energy for an attempt on Avachinsky instead was easy.

There has been some research into how group size affects the risk of involvement in avalanches: Risk of Avalanche Involvement in Winter Backcountry Recreation: The Advantage of Small Groups.

I found the following quotes from this research interesting:

We found higher avalanche risk for groups of 4 or more people and lower risk for people traveling alone and in groups of 2. The relative risk of group size 4, 5, and 6 was higher compared with the reference group size of 2 in the Swiss and Italian dataset. The relative risk for people traveling alone was not significantly different compared with the reference group size of 2 in the Italian dataset but was lower in the Swiss dataset.

Group decision-making is a highly complex topic and there is no empirical evidence whether groups make better decisions than individuals or if group decision-making pitfalls prevail.

The avalanche safety community should discuss how to advise recreationists who travel alone because data suggest that many people do travel alone despite the potential consequences; it is also unclear how avoiding some of the pitfalls of group dynamics and decision-making may affect risk for solo travelers.

I've personally noticed that while travelling alone you have less distractions, and you are more keenly aware of your own vulnerability. There is no-one to talk to or take photos of, so you listen to the snow, and watch your environment instead, constantly running the plan over in your head. This also makes it less fun in some ways, sharing the experience with others is very enjoyable.

There always seems to be a compromise between the need for speed/efficiency which equals safety in some respects and the need to stop and take stock of the situation and possibly take a longer alternative route which offers safety in other respects. I have been in situations where my partners have slowed us down considerably (and I have also slowed my partners down at other times). I have also been in situations where I felt the need to stop the group and argue that we needed to take the time to look under the snow to double check our assumptions about the conditions. It's an awful feeling when you compromise on your own values and sway with the group, everyone is aware that even just having the argument wastes precious time.

There seems to be some benefits to travelling alone, but it's also clear that it introduces some extra risk over travelling in an experienced and sensible group of 3 or 4, who you can bounce ideas off and collaborate with effectively. I feel like the most important thing is to always try to be aware of the actual risks involved, and the actual benefits that having partners, rescue equipment, etc, provides in your given scenario, and to constantly adjust plans and expectations to ensure that you stay within your personal risk appetite/plan.

When I reached the Avachinsky base in the early afternoon I was directed over to one of the other bases, it was empty, being managed by a friendly man named Ivan. I found a way to charge my devices using the USB slot on the TV before the power cut, and had a comfortable and warm night before waking up early to yet another perfect morning to make tracks up Avachinsky before sunrise.

I chose a route which stuck to the ridge line, free of exposure to slides, covered in sastrugi, and swept by an increasing wind. Near the top of the ridge the lack of snow once again necessitated the removal of skis, and several steps across volcanic soil before reaching a saddle/plateau. Here the wind was absolutely whipping and I kept moving to stay warm.

The final slope up to the summit of Avachinsky is definitely steep enough to slide, however it quickly became clear that most of the snow had been removed by the wind, and crampons were necessary for the final 700m vertical meters of altitude. The slope seemed endless and I was close to exceeding my turn-around time when the huge plumes of smoke came into view once again and I stepped up onto the rim of the crater, plunging steps through a thin layer of ice over warm and muddy soil. It was an incredible feeling being up there, face covered in ice and the view over to the impressive Koryaksky is unmatched. I didn't stop for long, after downing a Snickers bar I scratched my way down the ice crust and was able to ski almost from the summit, making use of a small wind drift behind a small line feature which drapes itself over that side of the volcano. Once gaining the plateau, I opened up the throttle until reaching a choke point where the slope steepens once again.

It was a decision point, I committed to a line, but stopped above the final steep slope to dig a pit, there was some wind/storm slab here of concern with a steep roll-over terrain feature below me. I was about to climb back up again the way I had come to retrace my morning route, when a little exploration to the left yielded a way which avoided almost all of the exposure, and I cruised on down back to the base, a perfect day to cap off an amazing trip.

The following morning I skied my way out to the road pleasantly surprised to be greeted by my Anna's friend Anna (who is on the Russian ski mountaineering team) with a 4WD to pick me up not long after she had just arrived home from a competition trip abroad.

A couple of weeks later I was able to join forces with Alexei to climb and ski Kozelsky, making it a skyline trifecta. Koryaksky summit can wait for another day, I'm pretty well convinced it will be even more fun in warmer conditions!

On a side note I created this video recently about the season in Kamchatka:

I'm currently living in Gudauri, Georgia with Anna, having just made it into the country before the borders closed due to COVID-19, and my Russian visa would have expired soon thereafter. Hoping to write more soon about the season in Kamchatka, and our last minute dash to Georgia!